“In a real sense, self inquiry is a spiritually induced form of winter-time. It’s not about looking for a right answer so much as stripping away and letting you see what is not necessary, what you can do without, what you are without your leaves. In human beings, we do not call these leaves. We call them ideas, concepts, attachments, and conditioning. All of this forms your identity. Wouldn’t it be terrible if the trees outside identified themselves by their leaves? These are very flimsy things to be attached to.”

– Adyshanti (from Emptiness Dancing)

Since my last post, a few close friends have made contact to share their own experiences of when physical and emotional challenges have converged in their lives. Embedded within their descriptions were suggested avenues for exploration to help me move forward, both on the bike and in my thinking.

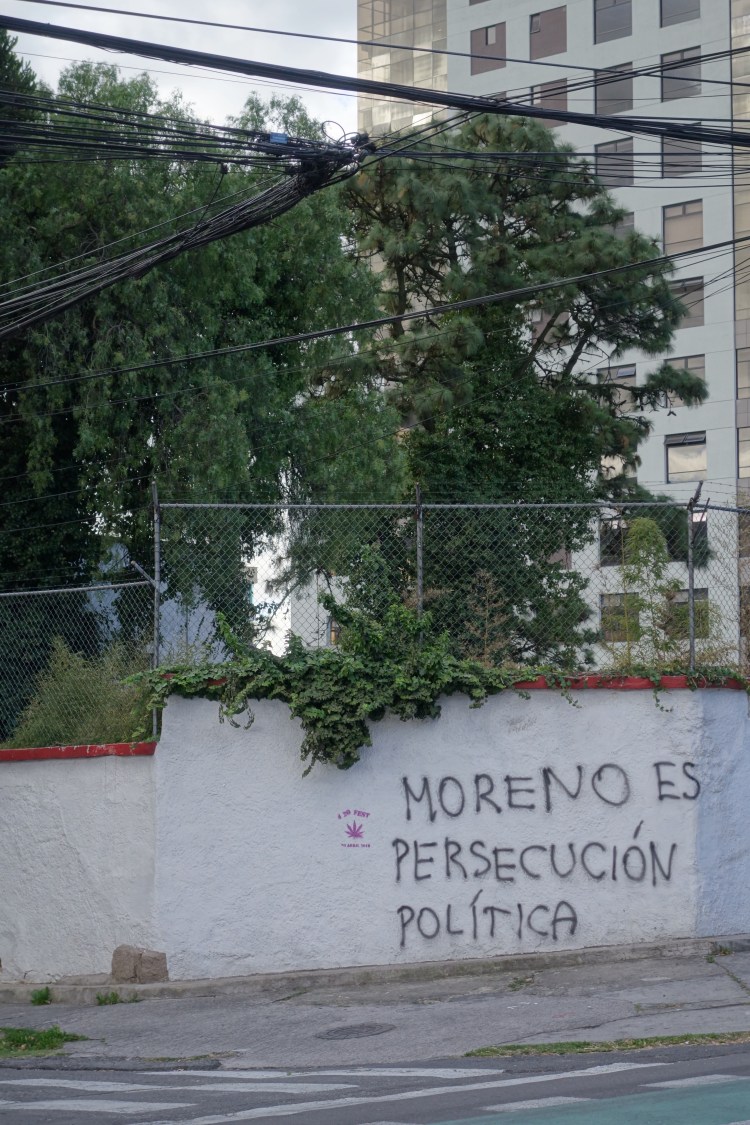

The passage above was sent to me by a friend with whom I have dissected many books and various strategies for introspection over the last few years. The concept of stripping back our temporary, seasonal attachments and exposing our true selves to the elements, is one that resonated strongly with me during the few bedridden days I spent in Quito. I have previously expressed that I didn’t set out on this trip with expectations of enlightenment, or anything of the sort. However, I have quickly come to learn that self-inquiry is an inevitable product of spending long days alone in the saddle. Perhaps it was the bout of gastro combined the with the absence of homely comforts, but I have never felt so vulnerable in my life. This vulnerability certainly blew all the leaves off my tree, forcing a connection between body and mind that was bordering on visceral.

Naturally, yet reassuringly, I overcame the brief illness. And, at risk of flirting with the cliché, I feel so much stronger in every way. My time in Quito was predominantly spent on my back, in bed or reading under the shade of a conifer in one of the many green spaces within the city. On my last day in the capital, I took a bus to the centre of the world before resuming my southern trajectory. Within kilometres from the highest capital city in the world, snow-capped volcanos appeared on the horizon, planting the seed for a love affair with Ecuador which is growing every day. I have reached new heights, expanded my lungs and made new friends along the way. The last week has reiterated that the easiest part of this trip will be the cycling, but for now, I can confidently say that I’m back on the bike.

Whilst this journey will provide me with ample time for reflection and self development, I am determined that for the most part, it is simply fun. The same friend as above concluded her message with this lighthearted, yet empowering sentiment, which I will carry with me until Argentina:

‘One is not the witness of a ‘real’ world; one is actually the source of its seeming reality. The world is actually entertainment. Like amusement, it is meant to be worn lightly.’

Centred.

Centred.

There are 55 species of Hummingbirds registered in the Quito Metropolitan Zone. Having only moved between the bed and the bathroom for a few days, I was determined to get out of my room and take inspiration from these enigmatic aves; the only birds that can fly in all directions, including backwards whilst upside down.

I never saw one.

However, the prospect of a sighting ensured that I wandered the city with eyes wide open. Quito, sitting at 2850m.a.s.l, is the second highest capital city in the world. Stretched out over 50km from north to south, Quito lies in the Guayllabamba River valley. Its linear layout is dictated by the mountains that lie either side; the volcanoes of Royal Cordillera to the east and the slopes of Pichincha, another volcano, to the west. Much like Bogotá, this ensured simple navigation, which was a blessing given my depleted cognition. Also following in Bogotá’s footsteps, Quito has adopted the tradition of a Sunday ciclovia. I slowly wandered the sidewalk in the opposite direction to the flow of human powered traffic. A motley peloton of unicyclists, rollerbladers and walkers with boom boxes on their shoulders, made for an entertaining excursion. The cycling path took me into the heart of one of the city’s most prominent parks – Parque El Ejido. The festivities occurring beneath the trees further explained the absence of people throughout the rest of the city.

I settled in beneath a tree with my book and woke an hour later after an unexpected snooze. A groggy lap of the park took me past a traditional dance performance, street performers entertaining crowds within grass-lined amphitheatres, overcrowded benches with elderly men engaged in heated card games, food vendors, and playgrounds which had the 5 year-old within quivering with excitement. The peripheries of the lively park were lined with artists selling their suspiciously similar paintings and coca leaf etchings. The overbearing soundtrack was being provided by a father-daughter duo belting out a panpipe, guitar and vocal version of the Cranberries’ ‘Zombie’. Strangely, I heard this song over a dozen times during my few days in Quito. The Cranberries are either experiencing an epic Latin American revival, or it has taken a while for Ecuadorians to warm to Dolores’ unique shrill.

Still lacking the energy to roam too far, I was swept up in the various artisanal markets that line the streets of Quito’s gringo capital, La Mariscal. Despite being obvious tourist traps, I enjoyed navigating the narrow lanes between stalls, ducking beneath pashmina garments as though I was passing into a Latino Narnia.

My appetite for local Ecuadorian cuisine was still a few days away, so I resorted to cooking simple pasta dishes back at my accomodation. Whilst preparing a range of vegetables which surely held the secret to my recovery, I got talking to one of the hostel’s weekend staff members, Joe. Like many people who study English, Joe’s handle of the language and its various nuances was phenomenal. This made for informative conversation, illuminating and explaining many of my observations over the last few weeks.

Joe was studying Ecotourism, a field which he argued was growing rapidly in Ecuador. We expressed shared concerns of how our respective governments are managing a somewhat similar economic transition from primary industries to services such as tourism. His knowledge of Australia’s love affair with finite resources and South Australia’s subsequent reliance on Elon Musk, was impressive.

On my last morning in Quito, I decided to visit Mitad Del Mundo; a monument erected in honour of the first geodesic mission and also the location of the equator. Despite the fact that the monument has been proven to be a couple of kilometres off the actual equator, the geographer within was itching to learn more about the key figures and techniques that were used during this initial expedition. As I was leaving the hostel, I ran into Joe and enquired about which bus I should take. He said that if I gave him ten minutes to wrap up his shift, he’ll take me there as he lives within a few hundred meters of the monument. Given this was a 90-minute trip that involved three bus changes, I was grateful for the guidance. Even more enticing, however, was the fact we could resume our conversation from the night before.

During the trip towards 0 degrees, we began discussing the crisis that is currently engulfing Venezuela, and consequently, the majority of other South American nations. Since 1991, a South American trade bloc known as the MERCOSUR agreement has been in existence. Despite various changes in member countries over the years, MERCOSUR’s purpose is to promote free trade and the fluid movement of goods, people, and currency between its associate nations (Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Venezuela and Suriname). As a result, citizens of these countries can reside in another member state for up to two years by simply providing an identification document and proof of a clean criminal record for the last five years. This explains why I witnessed so many Venezuelans moving freely through Colombia, whether atop trucks or walking along the highway. It also eliminates my confusion as to why so many people were crossing the border without showing a passport.

Joe went on to add that a few days prior, the government of Ecuador had introduced new legislation in which people could only enter the country with a passport. Whilst this still honours the MERCOSUR agreement, it will also limit the flow of Venezuelans into Ecuador, who have received over 100,000 Venezuelan migrants over the last two years. The hyperinflation that has occurred in Venezuela has rendered people unable to afford food, let alone apply and pay for a passport if they are not fortunate enough to already possess one. This additional piece of information also shone a light on something elseI had recently observed. When on the bus from Tulcan to Quito, there were several police checkpoints, in which armed policemen would inspect the luggage holds and ask to see passengers’ passports. Those who were both not Ecuadorian and unable to display a passport were removed from the bus. Upon reflection, this bus trip was the day after the new migration legislation was introduced. What I was witnessing was the dreams of a new life being pulled from beneath these people, who had left everything they knew to give themselves the best chance at a new life. I have heard that the majority of Venezuelas are trying to reach Peru, where it is thought that their savings will be considerably more profitable than within the USD economy of Ecuador. Therefore, the Ecuadorian government’s decision has thrown a spanner in the works for many of the migrants. As a result, the decrease in people crossing the border has simply seen an increase in applications for humanitarian passage through Ecuador.

What intrigued me most about Joe’s understanding of local, national and global politics, was his knowledge and interest in the foundation and drivers of many problems facing the world. Not only was he acutely aware of the Venezuelan crisis, but he also possessed an interesting theory as to why Argentina was not an associate nation of MERCOSUR, and subsequently would not be accepting migrants through a freedom of passage treaty. He explained how a number of ex-NAZI officials had resettled in Argentina at the conclusion of World War II. Not only did they relocate in search of a new life, but many of them paid their way into positions within the government of Argentina. Joe credited this phenomenon with the planting of xenophobic seeds within Argentinian society, which he boldly dubbed as ‘one of the most racist countries in South America’. Interestingly, in the following breath, he expressed his disappointment that Ecuador’s first president was in fact Venezuelan and how everyone throughout the country continues to celebrate Simon Bolivar, who was a traitor himself.

Joe’s company certainly made the 90-minute bus ride seem much shorter. A few stops before Mitad Del Mundo, he suddenly stood up and waved goodbye as he stepped off the bus. Our conversation had concluded with a quick comparison of our respective nations’ current political situations. Joe described a past president who, upon being elected, arrived at his first national address by sliding down a rope from a helicopter, dressed as Batman. Ideally, this should have made me feel fortunate about the ‘stable, equitable government’ of the well-developed country which I call home. Unfortunately, given the last few weeks back home I couldn’t bring myself to feel so lucky.

Minutes after Joe had left me with my thoughts, the ticket collector on the bus announced that we had arrived at Mitad Del Mundo – the Middle of the World Village. An avenue of busts representing all the members of the first geodesic mission lead to the central monument; a square based tower adorned with an enormous, 5-ton globe. I climbed the stairs to the observation deck, eager to feel centred. Ironically, the view to the east was of a bare hill capped with a small trig point marking the actual location of the equator. The wind was whipping the dust up out of the valley below, marring the view of the world’s real centre, so my attention was drawn back to the hoards of people below taking pictures of the yellow-painted equatorial line which dissected the village.

The descent from the top of the tower took me by various scientific displays; gyroscopes, light displays investigating seasonal sun paths, and an explanation of the Coriolis effect, debunking the myth that water will spin down the sink in opposite directions in either hemisphere. Trying to process this buzzkill, I spent some time exploring the ‘village’.

The site had been developed as a ploy to draw more people to the site of the first geodesic mission. Based on this logic, I was left a little baffled by the final product. There was an assortment of displays and gift shops with very little, if any, relevance to the equatorial location of the site. I wandered through a brewery museum, an augmented reality exhibition of pixelated animals from the Galapagos, and a planetarium. Admittedly, there was quite a fascinating cacao museum on the outskirts of the site. The girl facilitating the display was clearly happy to have someone pass through. She explained the various stages of fermentation that the cacao is exposed to, before being sun dried and toasted. She let me smell and taste the seeds at various stages, with the flavour and aroma intensifying as the seeds were stripped of moisture.

Buzzing from cacao, I jumped back on a bus. Unfortunately, the conversation with Joe had distracted me from keeping an eye on which busses to catch. Two hours and a few figure-of-eights later, I stepped off the bus in the heart of Quito’s historical centre. This UNESCO listed site made for a mesmerising stroll. The colonial architecture, humbling church spires, narrow streets and carved, wooden balcony handrails made it easy to lose a few hours.

I made it back to the hostel as the sun was setting over Pichincha, casting a twilight glow over the city. I spent some time doing a little bike maintenance and reconfiguring the weight distribution within my panniers. Still struggling slightly with the scale of this journey, I was certainly in better health than when I arrived in Ecuador’s capital. And, with my first impressions of this country marred by a turbulent stomach, I was hanging out to see what the road ahead had to offer.

‘The Neck of the Moon’

The ride out of Quito was far from the greener pastures I was seeking. The exhaust from passing trucks was thick, and the air was thin, making the constant climb out of the city incredibly challenging. Throw in a persistent headwind resulting in an average speed of 10km/h, and it was a relatively uninspiring day on the bike. However, as is so often the case with cycle touring, things can change in an instant. After 70 kilometres on the Pan-American highway, I turned off towards Cotopaxi National Park and, within minutes, arrived at a quaint, shingle-clad guest house. The Rondador Cotopaxi was positioned several kilometres from the entrance to the National Park, and over two kilometres below the summit of Volcan Cotopaxi – Ecuador’s second-highest peak. I was greeted by one of the owners, Jenny, who was happy to let me camp in their back yard. The only catch was that I had to share the lawn with Jaunita, their beloved pet llama. There were a few territorially issues to iron out at first, but after we broke the ice over a few carrots, Jaunita was accommodating for the remainder of my stay.

Jenny and her partner, Fernando, were the perfect hosts; relaxed, informative, interesting and interested. They would let me stay up writing by the fire at night until the last fading embers indicated it was time to sleep. Fernando performed a captivating demonstration of various traditional instruments. There were panpipes of different sizes and configurations, as well as a range of stringed instruments. One of these, mandolin-like in sound and shape, had a body made of an armadillo shell. Having seen my first armadillo only days before, I certainly didn’t expect that this would be my second sighting.

I ended up staying at the Rondador for two nights. During the middle day, I was able to put my bike in the back of a passing Ute, and score a lift into the national park, where I was dropped at the base of the volcano. The wind above the tree line made it difficult to swing open the door of the Ute. I left the car park and began the ascent to the climbers’ refugio; a lodge which acts as base camp for those beginning their midnight ascent to the summit of the 5897m volcano. With the campsite at the Rondador being my highest elevation of the trip to date (3150m), the walk up the slopes of volcanic sand and rock felt as though I’d recently donated a lung. The wind only increased in ferocity as I climbed higher, often resulting in a stumble backwards as I lost precious metres of progress. However, any frustration that began to seep into my thoughts was blown away on the wind as Cotopaxi began to reveal its snow covered summit. As the sky cleared, it became difficult to tell where the clouds ended and the glaciers started as they flowed down from the conical peak. Stretching towards to sky, it was easy to see why Volcan Cotopaxi is known at the ‘neck of the moon’.

I settled in at the refugio, tucked into a corner with a window to my left offering a view of the valley below, and to my right, a stream of other wind-burnt walkers entering the room, eager to put the heavy wooden door between themselves and the elements outside. After an hour of watching people escape the wind, yet unable to distance themselves from the lack of oxygen as they breathlessly ordered hot chocolates, I pushed on the the base of a glacier, at 5100m.

During my drive up to the national park, the lady giving me a lift had been discussing the state of Ecuadorian glaciers. She was an alpinist, and only the day before had been standing atop Chimborazo, Ecuador’s highest point and, interestingly, the furthest point from the centre of the earth due to the equatorial bulge of the globe. She told me that it was her second time standing on the summit of Chimborazo, the first being four years before. She went on to say that this time, the summit was nearly 100 metres lower due to the rapid melting of ice and snow in Ecuador’s high areas. These regions already have to deal with the intensity of the equatorial sun, as well as the internal heat of the volcanos upon which the snow and ice accumulate to form glaciers. Throw in a changing climate and many equatorial glaciers, of which a number of communities rely on as water sources, are facing an enormous challenge.

Upon reaching the edge of the ice, the summit came into full view. The thick snow mushroom created a wondrous contrast against the red, grey and brown soils that comprised the slopes of the volcano. The mountain air, albeit thin, was refreshing and empowering. As I made my way down the side of Cotopaxi, I was revelling in the extra oxygen reaching my lungs and brain, awestruck by the landscape below that was now almost completely clear of cloud.

The remainder of my afternoon was spent leisurely wandering the perimeter of Laguna de Limpiopunga. This shallow Andean lake, sitting at 3830m, was filled with coots, desperately trying to maintain their forward momentum as gusts of wind lashed at the water’s surface. The edge of the lake was home to an enthralling floral display of hardy, sub-alpine species. Enjoying the macro-level attractions that the National Park had on offer took up a good few hours.

With the sun beginning to fall behind the mountains, and the park closing within the hour, I jumped back on the bike and held on for the descent back down into the valley, past grazing wild horses, to my tent. As I sat by the fire that night with a sweet black tea on the arm of the couch, I scanned the route ahead on a variety of different maps. Having had such a reaffirming day in the mountains, I decided that another detour from the road south was exactly what I needed. Over the next three days, I set my mind on tackling the Quilatoa Loop; a road that winds its way past volcanic crater lakes and connects various highland villages. This decision was a strong ‘move towards myself’ moment. Simply racing south towards a preconceived destination is far from the reason I am on this continent at all. I am here to be replenished by wild alpine sounds and seek the humility that seeps out of small mountain towns. I was hopeful that the Quilatoa Loop would afford me with both of these.

A Loop and a Lake

I cycled away from the Rondador with a pannier half full of bananas; a parting gift from Fernando. The sky was clear and the breeze was fresh and strengthening. Cotopaxi was a constant presence on the horizon for the entire day.

Following a brief few kilometres on the Pan-American, I took a turnoff towards Sigchos; the starting point for those who hike the trails of the Quilatoa Loop. From the moment I left the highway, I felt a sense of calm. The quiet country roads, lined with various crops and welcoming locals, provided a phenomenal and much needed change of pace. Over the course of the afternoon, the route continued to climb and the surrounding peaks began to reveal themselves. The grazing cattle slowly raised their heads from the dense pasture as I cycled past, and the country dogs were less inclined to chase me down like their city-dwelling counterparts. Between the climbs, long, switchbacking descents would carry me to the bottom of valleys, where clear streams flowed beneath narrow, one-way bridges. The mosaic hillsides of various shades of brown and green, contrasted spectacularly against fields of dandelions. After a less than ideal introduction, I was quickly developing a love affair with Ecuador.

The final descent for the day was mirrored on the other side of the valley by several switchbacks climbing up to the centre of Sigchos. Despite the allure of the cobblestone streets and views over the surrounding peaks in the afternoon light, I decided to push past Sigchos and knock a few kilometres off the next day’s climb. Within half an hour, I rounded a forested embankment to find a boutique hotel sitting on the edge of a large eucalyptus forest. The receptionist offered me a campsite on the front lawn, in exchange for a few dollars and the job of entertaining the house dog. It sounded like the perfect deal. After a good wrestle, we both lay on the grass, soaking up the last of the sun before it fell behind the trees on the hill.

Despite only being 40km in distance, the middle day of the Quilatoa Loop was both the most gruelling and by far the most spectacular day of riding I had experienced since arriving in South America. As mentioned, the Quilatoa Loop is a popular hiking destination. However, walkers only pass through a few of the towns where the trail dissects the road, meaning that the road itself is incredibly quiet. Over the course of the day I saw less than a dozen vehicles. Given that the road surface was only a couple of years old, this made for superb riding.

The weather was sensational. Cloud free skies allowed the sun to illuminate the green hillsides and snow-capped peaks. The gentle alpine breeze ensured the climbs were pleasantly cool and the views into the steep valleys below completely distracted me from the fact I was climbing. I stopped in a small town called Chugchilan for a tortilla filled with peanut butter and one of Fernando’s final bananas. As I sat reenergising and observing the lack of OH&S at a building site across the road, I was joined by a rather forthcoming, yet friendly, man named Carlos. He was on his lunch break from work, were he was the English teacher at the local school. Over our respective snacks, we discussed the shared frustration of teaching students who simply don’t want to be there. After half an hour, we still didn’t have the answer for this evidently universal challenge. Still, he optimistically headed back to the classroom, summoning a few of his students from the basketball court as he passed.

From Chigchilan, the remainder of the day was in a steady upwards direction. As I climbed above the tree line, the vegetation began to give way to the slate-grey bedrock, reminiscent of the Sierra Nevada that inspired the likes of Jon Muir. I overtook a young boy shepherding his goats up the road, only to stop for a break at the top of the climb to be overtaken again. With just his dog, gumboots and a bamboo cane, I could see in his eyes that he was questioning my need for a fancy bike to get up the hill.

Over the course of the afternoon, there were two sustained climbs at around 10-15%, before the grand finale; a two kilometre long incline at 17%. This section of road dissected the hillside, with the steep slopes of the road cutting acting as a wind tunnel for the breeze that had stiffened tremendously over the day. After persevering for several minutes, I was reduced to pushing for the first time this trip. This proved equally as challenging as being in the saddle, as I picked targets in the distance where upon reaching them I would give myself a break. By the time I reached the saddle, I was at around 4200m and my legs and lungs were screaming. However, given my struggle climbing out of Quito a few days prior, it was clear that the day acclimatising at Cotopaxi had paid off as I was feeling relatively strong cycling at this new altitude.

Fortunately, from the top of this hazing climb, it was a 500m roll down into the town of Quilatoa. This town is where the road and the walking trails converge, as the views over the volcanic crater lake below are breathtaking. The vista is reminiscent of Tassie’s over-Instagrammed Lake Oberon, but on a much grander scale. After the day of climbing that I’d had, the trails down from the rim to the lake’s edge were beyond me. The wind was now tearing across the ridge tops causing the temperature to drop into the single digits. I zipped up my jacket and watched as the fading sunlight, combined with the rapidly moving clouds, threw emerald green patches across the surface of the water. This twilight disco culminated in the rising of the full moon, emphasising that it was probably time to find somewhere to pitch the tent.

With limited options and several overpriced hostels, I was stoked when I the owner of a hotel with ample lawn space, showed me where I could set up my tent in the lee of the building. As I pushed the poles through their canvas sleeves, my ears were ringing from the wind that had been blasting my face all day. To show my appreciation for the free campsite, I ate at the restaurant of the hotel. The $3 set-meal and glowing pot-belly fireplace warmed me from the inside out. I ate dinner with a Swiss couple, Daniel and Nadia, who pointed out the window to a stray dog which had followed them for the entirety of their 16 kilometre walk that day, only to be left outside in the dark upon arrival. It was no surprise that when I walked outside on my way to bed, I instantly gained a fluffy, one-foot tall shadow which curled up for the night beside my tent.

The following morning, neither I or my new four-legged friend were tempted to move until the sunlight reached where we were lying. As I packed up the tent, I could see from the grass beyond the hotel wall, that the wind had already woken up and was picking up where it left off the night before. Despite the fact I could count all his ribs, and he was clearly revelling in the morning sun, the dog picked himself up and ran beside me as I rolled out of town. I stopped to ruffle his head and suggest he goes back to bed, but he was persistent. As I picked up speed, he chased after me barking in desperation. Already feeling a little homesick, the separation anxiety was killing me. I have no doubt he would have stuck with me all day if I’d dropped the pace.

Within a few kilometres of leaving Quilatoa, the fields to my left split open, revealing a dramatic sandstone gorge which had been carved out by the Rio Zambahua. Standing amongst the pine forest on the edge of the gorge, with a photogenic llama tied to a tree beside me, I was completely awe stuck my the beauty of Ecuador. Within 200 kilometres from Quito, I had seen such a diverse range of landscapes, of which I felt a strong affinity with them all. Ecuador was quickly becoming my happy place.

New Friends and New Plans

Commencing what I thought was a day of ‘downhill’, I rode into a small town called Zambahua, nestled beneath a towering rocky outcrop. The town was teeming with people as the Sunday market was in full swing. This was quite excellent. Firstly, I love markets. Secondly, it was good to find out what day it was. The central plaza was bursting with colour as dozens of fruit and vegetable vendors were eagerly displaying their produce. The soundtrack of the town was provided by an upbeat big band, and the grunting from a heated game of volleyball.

As I stood on the corner looking over the festivities, I was approached by an American who introduced himself as David. He was quick to tell me that he was also cycling through Ecuador. As I have written about previously, bikes provide currency for conversation when on the road and this was one of those moments. David was cycling the TEMBR (Trans-Ecuadorian Mountain Bike Route) which takes in the backroads from Quito to El Dorado in the south. Yes, he was cycling the road to El Dorado.

He explained the last few days of the trail; over 100km of climbing on corrugated and cobblestone roads, with descents too rough to gain any speed. He had arrived in Zambahua earlier that morning and was happily settling in to his first rest day. I knew the feeling! Conversation quickly moved onto the emotions associated with solo cycle touring. Within minutes, David was checked out of his hostel and back on the road as we decided a few days cycling together would be a welcome break from the company of our own thoughts.

In deciding whether or not he would join me on what was going to be his rest day, I did mention to David that the day’s ride was predominantly downhill. Within half an hour of leaving town, we found ourselves facing an intensifying headwind and an elevation gain of over 1000 metres. It was brutal. The relief of the surrounding landscape was playing tricks with the wind direction. On a straight section of road it became common to be hit by a headwind, tailwind and crosswind all within the space of thirty seconds. This was more of a hazard than a frustration when on the descents, as the fully loaded bikes would catch the breeze demanding gritted teeth and a firm grip on the handlebars. On one particular climb, we were hit from behind by an epic gust of wind, causing my shirt to ride up my back whilst projecting me uphill at 25km/h!

We eventually crested the highest climb of the climb at around 4200 metres. As the road looped back towards the Pan-American highway, the summit of Volcan Cotopaxi came back into view, indicating that the Quilatoa Loop was coming to an end. During the late afternoon, my promise to David of a descent finally came to fruition as we emphatically navigated the switchbacks of, arguably, the best downhill stretch of road that I have ever ridden.

The descent shot us out into the town of Latacunga; a colonial town lined with cobblestone streets and providing a popular base for those hiking the Quilotoa Loop. A local music festival serenaded us as we rolled through the centre of town in search of a hostel. Once checked in and showered, we bonded over our love of eating as we ate our way around town. I’m still trying to decipher whether my insatiable appetite is due to a tape worm or the hours of cycling I’m doing each day. I’m sure it’s the later, but I’ve never eaten so much in my life.

The Call of the Amazon

Sitting in Latacunga, eating, David and I discussed our respective plans. He is in between jobs, starting work with the bike company Cannondale at the beginning of October. Despite coming down to ride the TEMBR, he is as happy as I am to have company for a while. Given the unsuitability of my setup for a mountain-bike route, he is also happy to join me on the sealed surfaces for a while. From here, we’re both excited to experience the mega-diversity on offer in Ecuador. We’re going to continue the descent from the mountainous highlands, and plunge into the depths of the Amazon Basin. Of course, this will culminate in another hectic climb back up into the Andes, but the fact Ecuador has more species of palms, and hummingbirds, than the rest of the world combined, makes the rainforest an alluring destination for the next week.

Thanks for reading.