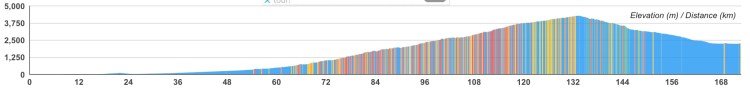

The language barrier had nothing to do with the predicament that I had landed myself in. Halfway up a 100km climb, from sea level to 4300m, I found myself short of breath and with a pannier full of peaches. Although the kilos of ripened fruit weighed me down, the gesture was overwhelming energising.

The coast had provided the rejuvenation I needed to launch back into the mountains. But, within minutes of dropping my chain to the smallest ring and loosing count of the switchbacks in the road above me, I knew I was back were I belong.

Over three days, the road traced a hairpin-infested line between the charcoal coloured crags of the Cordillera Negra. The slopes of the barren peaks were draped haphazardly in crops of wheat, maize and oats, separated by lichen coated rock walls. In crossing the Cordillera Negra, I reached the loftiest heights that I’ve ever been to on a bike. While the hills left my lungs feeling empty, the local encounters along the road filled my heart.

Hospitality in the hills

Each passing vehicle kicked a plume of sand and dust into the air. It was only 9am, yet a stiff southerly breeze had developed, whipping the particle laden air directly into my path. With sunglasses on and my face tightly wrapped in a bandana, the grit still managed to embed itself in my eyes. I pushed the discomfort aside and continued pedalling. I had been anticipating this day for a while now. After several days of riding into headwinds, my path dictated by the coastal geography, I only had 20km to ride from Chimbote before turning east and heading for the hills.

Within minutes of passing the city limits of Chimbote, I heard the familiar sound of a police siren. I’ve come to realise that this is no cause for concern in South America, as it is common for people to install car horns that replicate the sound of emergency response vehicles. However, this time the vehicle responsible for the sound, raced paced me, adorned in official insignia indicating that this was in fact the ‘Policia’. As quickly as it overtook me, the car pulled off the road and hit the brakes, disappearing in a cloud of dust and authority. When the wind cleared the scene, I was greeted by two officials, in neatly pressed uniforms, waving me off the road. The proceedings were very regimented. They asked to see my passport and took photos of my various other forms of documentation. Once this process was complete, it was as though a switch was flicked. Almost instantly, they regressed from their professional duties and their faces cracked into warm smiles. They were intrigued to know more about my route and did their best to fill the memory on their mobile phones with various photographic combinations; me with each of them, me with just my bike, me with their police car, my bike next to their car, just their car (not sure what this one was about?)…before they left, I turned the camera on them. As they got in their car, they double checked that I didn’t require a police escort for the remainder of the day’s ride.

A large roundabout marked the end of my journey along the Pan-American highway (for now), as I took the exit towards the town of Moro, which sits at the foothills of the Cordillera Negra. The road was narrow and flanked by crops of Totora and stone fruit orchards. The uncharacteristically fertile surrounds were the result of a network of gurgling water channels that had been diverted from the nearby rivers flowing out of the mountains. I welcomed the sensation of the wind on my back, averaging between 25-30km/h from the junction with the highway, all the way into Moro. A number of farmers were in the process of back-burning which, combined with the wind from the coast, marred the view of the horizon in an eggshell-blue haze. Retrospectively, this may have been a blessing as a clear day would have only exposed the immense vertical challenge that lay ahead of me over the next few days.

After five minutes in Moro, I had already ridden several laps of the town in search of a place to rest for the night. Of the three options, I settled for a small hospedaje, just off the main plaza. The owner was a gentle man who spent his time gliding the tiled hallways with his hands clasped in front of his hips. For half an hour after I arrived, he did laps by the door of my room to ensure that I was comfortable, which had the opposite result.

I spent the remainder of the afternoon in Moro settled in at Mundas’s Bar. Dimly lit and seemingly the only watering hole in town, the garage-like building opened up on to the main road, offering a great vantage point from which to watch Saturday night come to life. Upon sitting down, I ordered a cerveza. The barman promptly brought me my options; a Heineken or a Budweiser. My reddened face and equally rouge facial hair must have suggested that I was a gringo in need the taste of home. I paused, before gesturing to to the bottle of the local larger, Cristal, that the men beside me were drinking. He returned with the one litre longneck and a small glass. In appreciation of my preference for their national drop, the table of men across the bar raised their glasses in my direction.

The next morning, as I loaded my panniers in anticipation of what was to be the beginning of the ‘real’ climb, the owner of the hospedaje came to see me off. He gave me a handwritten letter for the owner of a hotel in the next town, and my destination that evening, Pamparomas. After an elongated handshake, in which he held my hand in both of his wishing me a safe onward journey, I straddled my bike and attempted to leave town.

Over the last few weeks, I have come to expect towns to remain asleep on Sundays, where the chance of picking up fresh supplies is as likely as snow in the Amazon. However, the streets of Moro were alive on this particular day of rest. Vibrant arrays of fruit and vegetable were spread along the side of the road. The local women, dressed in knee-length skirts, stockings, festively coloured cardigans and tall, felt hats, sat camouflaged amongst the fresh produce. Thick plastic crates held a plethora of fish species, disconcertingly positioned in full sunlight. Perhaps it was the Lycra, or the fact I was the only person having to duck my head when walking beneath the low hanging tarpaulin roof of the market place, but I seemed to attract the gaze of almost everyone that I passed. Whilst clawing through my wallet in search of the correct change for a bunch of bananas, I heard the first hint of English since being in Moro.

He introduced himself as Pablo. Baby-faced, with shoulder-length, black curls and both ears pierced with silver sleepers, Pablo’s personality was infectious. He listened attentively to every word that I spoke, offering measured responses and inquisitive questions which inspired the same level of focus from myself. Pablo explained how he and two other friends, who were still in bed, had been in Moro for one month, with another two still to come. They were on exchange from their university in Spain, completing the final component of their teaching degrees. Their weeks consisted of Tuk Tuk rides to various mountain communities in the region, where they would spend time with students, relieving the teachers who are commonly responsible for between 50-60 pupils each. We shared various anecdotes from classrooms within our respective countries, before the apprehension of the upcoming climb got the better of me. I thanked Pablo for introducing himself and wished him well for the rest of his time in Peru.

As I rode away, I couldn’t help but envy the relatively sedentary nature of Pablo’s experience. Whilst his stay is also temporary, there is an overwhelming sense of impermanence that comes with cycling through towns like Moro. I often find myself craving invisibility. What right do I have to thrust myself into a state of voluntary struggle, breathing heavily, as I ride a heavily laden bicycle past people who may travel no more than a hundred kilometres during their entire life? I’ve touched on this burdening sensation of privilege before. I’m not sure that it contributes positively to my experience, yet I trust the reflection will continue.

The ride from Moro to Pamparomas bordered on perfection. The foothills of the Cordillera Negra held on to the barrenness that I had come to know over the last few days on the coast. The steep slopes were covered in an unnaturally even distribution of sandy coloured boulders and cacti. After an hour or so of climbing, I stopped to look back of the valley from where I’d come. The aridity of the landscape below was clearly dissected by a ribbon of green. Starkly marking the presence of a river, the riparian vegetation emphasised life’s reliance on water. I gulped from my drink bottle, washing down a banana and a few cheeky Oreos, and continued upwards.

Traffic decreased as the road narrowed. The thin line of asphalt gently caressed the hillsides, with large sweeping bends dictated by the contours of dry creek beds leading to the valley below. The gradient was kind, although it never let me forget that I was climbing. From the edge of the road I could see vultures circling below me, while the mountains above grew taller.

Following a brief stop for a lunch of avocado and sardines, a motorbike passed me before pulling over to the side of the road. The driver smiled and nudged his pillion passenger, who I assume was his daughter. She reached into the small backpack strapped to her front, and pulled out a large papaya. She handed it to me before they sped off waving goodbye. I figured a little lunchtime dessert would be a welcome treat, plus the idea of lugging a papaya up the road was less than appealing. I cut into it with my knife, only to discover that it was a few days from being ripe. Convinced I was being watched, I looked both ways before guiltily hiding the papaya behind a rock on the side of the road and riding away. I hoped they would understand.

The afternoon turned into a scorcher. Haze emanated from the road ahead and I soon found myself sucking the last drops of water from my bottles. I passed a row of three houses, where a family seemed to be in the midst of their Sunday laundry routine. I pulled over and they gladly filled my water bottles. As I rode away, a heard a voice shouting in my direction. Turning around, I saw that it belonged to a man running up the road behind me. With his flannel shirt tucked into his well worn denim jeans, he was struggling to keep his thongs from falling from his feet whilst one hand held his hat from flying off in the wind. I cut him a break and stopped to let him catch up. I couldn’t quite make out what he was saying, but I gathered from the way he was pulling on my handle bars and pointing back to the houses, that he wanted me to return with him.

I quickly got the sense that he was the life of the party in this small hamlet. As we walked up the concrete steps to the front of the house, the other people just sat smiling, shaking their heads and raising their eyebrows. Inside the shed attached to the side of the house, were dozens of crates filled with peaches. He pointed out towards the orchard on the other side of the road, proudly showing off his produce. Without question, he reached for a plastic bag and began filling it with the golden fruit. When he handed me the bag, which he needed both hands to lift, I laughed, explaining that there was no way I could carry that with my on my bike! The ladies around him emphasised the point and he nodded in agreement, proceeding to remove a total of half a dozen peaches, before handing back the bag. His excitement was infectious, and the gesture was overwhelming. After a series of photos with the younger girls, who blushed in embarrassment when the man kept asking me if I thought they were beautiful, I strapped the bag of peaches to my rear panniers and pedalled away. Now with an additional five kilos of fruit on board, I couldn’t help but think it was an act of karma from the gods of fructose, punishing me for leaving a perfectly good papaya on the roadside earlier in the day.

The final few kilometres to Pamparomas involved of a series of switchbacks. Looking towards the coast, the afternoon sky began to transitioned to the twilight hue of lavender. Rows of silhouetted ridge lines indicated how far inland I had ridden. I rounded the final bend for the day, presented with a view of the town, tucked into the hillside and drenched in the afternoon sun. I was stopped on the edge of town by three young boys who wanted to know what purpose each component on my bike served. Once the demonstration had finished, they asked where I was staying. I pulled out the now scrunched piece of paper from the hotel owner in Moro, and handed it over them. Resounding ‘ahhhs’ suggested they knew where it was. The two eldest boys moved in on either side of my bike, prying it from my grip and demanding that they lead me to my accommodation. I felt slightly self conscious as I walked behind them through the centre of town under the watchful eye of locals, but again, the hospitality of the mountains was proving to be unforgettable.

The final few kilometres to Pamparomas involved of a series of switchbacks. Looking towards the coast, the afternoon sky began to transitioned to the twilight hue of lavender. Rows of silhouetted ridge lines indicated how far inland I had ridden. I rounded the final bend for the day, presented with a view of the town, tucked into the hillside and drenched in the afternoon sun. I was stopped on the edge of town by three young boys who wanted to know what purpose each component on my bike served. Once the demonstration had finished, they asked where I was staying. I pulled out the now scrunched piece of paper from the hotel owner in Moro, and handed it over them. Resounding ‘ahhhs’ suggested they knew where it was. The two eldest boys moved in on either side of my bike, prying it from my grip and demanding that they lead me to my accommodation. I felt slightly self conscious as I walked behind them through the centre of town under the watchful eye of locals, but again, the hospitality of the mountains was proving to be unforgettable.

I thanked the boys, who, by the time we reached the hospedaje had broken into a sweat. I promise I offered to help. I was greeted at the door by Rosa, the owner, who smiled when she read the note I’d carried from Moro. Seemingly in a rush, Rosa showed me the room and told me she’d catch up with me later. I dropped my panniers and quickly headed back out into the streets to catch the last light on the mountains. The most notable features of the town were its tidiness and the steep gradient of its streets. The central plaza was lined with meticulously well-kept hedges, and rubbish bins on every corner. I pushed the feeling of my fatigued legs aside as I watched a number of elderly residents wander the streets, aided by walking sticks or the supportive arms of a younger family member. Once the sun had disappeared, I returned to the hospedaje, where I was handed a cup of purple jelly (an increasingly common dessert in Peru) and told to take a seat by the young couple working in the kitchen. Over the next hour or so, I was truly doted over. Just as a plate of rice, eggs an fried plantain was placed in front of me, Rosa reappeared and took the seat across the table.

I was surprised by how well she spoke English. She explained to me that she had lived in California with her young daughter and her sisters. However, when her mother fell sick she took it upon herself to return to Pamparomas and care for her. The rest of her family, including her daughter, chose to stay in the California, where they remain today. She told me how at first she had been excited to return to Peru. She had plans of starting a Cuy (Guinea Pig) farm on her family’s land, where she would also grow crops of alfalfa to fatten up the animals (they are a delicacy in Peru). Unfortunately, when she returned, she discovered that times had changed since she had left. She found it impossible to find anyone willing to work for her. All of the young people had left for the city, and those that remained weren’t interested in physical labour. As a result, she developed the guest house, which, until recently, she has managed to support on her own. She went on to tell me that she is growing increasingly tired of how quiet Pamparomas is (“there’s not even a cinema”), and is spending more and more time at her other house down in Chimbote. That was when she pointed at the young couple in the kitchen, with a smile on her face, explaining how it was their first day of work as they only arrived yesterday. The couple were from Venezuela and had met Rosa in Chimbote a few days before. Eager for work and the chance to establish a new life for themselves, they had excitedly accepted the offer to return to Pamparomas with Rosa and learn the ropes in running the hospedaje. Rosa has plans to visit her daughter in California in October, and is hopeful that she can leave the place in the hands of the two delightful Venezualans. Given their eagerness to please, I doubt she will have an concerns.

From Pamparomas, there was still 1500 metres of climbing between me and the highest point of the road. It was only fitting that I left the bag of peaches in the kitchen as a parting gift.

A cerebral marathon

Whether bushwalking or cycling, I have always hated stopping halfway up a hill. More psychological than physical, it just makes so much more sense to rest at the top. In the case of crossing the Cordillera Negra, I had no option but to spend a night halfway up the hill in Pamparomas.

Getting back on the bike the day after a long day of climbing, is like waking up next to a lover having gone to bed after a petty argument. You might pretend to be holding onto emotions from the night before, sullenly moping around each other, until something humorous occurs. You don’t want to be the first one to laugh, giving into the ‘bigger’ issue at hand. But, once you make eye contact, you’re both enveloped by laughter, rendering the initial argument completely irrelevant. You still love each other, so you quickly move on.

My legs screamed at me upon the first pedal stroke away from Pamparomas. By body ached, and I blamed the bike for every discomfort.

“Why can’t your tyres be more inflated? You’re wasting my energy”, I silently said to my bike, accusing her at any opportunity. “I know you meant to slip gears then, you want me to suffer”.

But, just like those petty arguments, it only took the first view of the mountains in the distance for us to push our differences aside and realise how happy we both were to be there. Towards the top of the climb, the road flattened out the landscape became much greener. The rain shadow effect of the Cordillera Negra was becoming increasingly evident. Precipitation rolls in from the Pacific, pushed up the hillsides as it builds energy, releasing the built up moisture as it crests the peaks. Clear streams ran between grassy fields, where grazing cattle and thick coated sheep became prolific. I was stopped by an old toothless farmer, with a pitchfork over his shoulder. One of the most outwardly happy people I think I’ve ever encountered, he introduced himself as Thomas. He told me that in all my travels I’ll never forget him as his name sounds like ‘tomatoes’. He was very pleased with this logic.

The final few kilometres of the climb were a struggle. Having crossed the 4000m mark, the air was noticeably thinner. Whilst my breathing didn’t seem to be too affected, my cognition began to suffer. I struggled to keep my wheels tracking in a straight line, managing to hit every pothole and corrugation. Trying desperately to think coherently, I became stuck on simple words and phrases which cycled through my mind on repeat. Altitude is certainly a cheap high.

Around 4pm, I crested the pass at 4314 metres above sea level. I sat for a while devouring my final banana and a handful of crackers. Given the final 40km to Caraz involved a 2000m descent, I figured I had time to kill to take in the view. This logic couldn’t have been more wrong.

As soon as I began down the other side, I passed a turnoff to a mine. The road on this side of the pass clearly sees a lot of heavy traffic as the road was in atrocious condition. Each of the steep hairpin bends was covered in deep, soft sand, requiring motocross skills as I placed my inside foot on the ground guiding the bike safely around each corner. The straight sections of road were coated in a thick orange clay. Despite the testing conditions, it required all of my energy to keep my eyes on the road and refrain from getting absorbed in the landscape below. The gradient of the hillside was so steep that the switchbacks below appeared like a vertigo inducing staircase, where your feet are longer than the stairs are wide. On the adjacent side of the valley was a steep, shard-like face of rock and, what appeared from where I was, a near vertical grassy slope. Beyond comprehension, the green hillside was into crops.

From the top of the valley I could see the town of Caraz. Thunder began to resonate up the gorge below me as heavy drops of rain started to fall. The snow capped peaks of the Cordillera Blanca to the east, were swallowed by the bruised sky which carried the rainstorm in my direction. My wrists ached from the perpetual braking and the tight grip required to keep me from taking a much quicker, yet less desirable route, to the valley floor. In a lapse of concentration, and on an especially muddy corner, I came unstuck. Falling hard on my right side, I lay on the ground collecting my thoughts and completing the standard ‘what is broken’ body scan. Fortunately, the result was just torn clothes and a bloodied elbow.

I limped down the remainder of the descent, eventually rejoining the paved road and rolling into Caraz on dark. My body and bike were caked in a thick layer of dust and mud when I walked into the reception of Hostel San Marco. A single room set me back $6 a night so I booked for three. Bloodied, bruised and back in the mountains, I was super excited to spend a few days checking out the region. However, following a shower and a quick dinner, this thought was put on hold as I was overcome by sleep.

Thanks for reading.