El Chalten had been the last dot point on what had originally seemed like an endless list of ‘must see’ places along the journey. With this ‘list’ accomplished, neither of us had any lingering expectations or needs to fulfil. All that remained was the desire to maximise what was left of the time we had together travelling as father and son. Tracing a finger along the road south, the contours on the map suggested a barren landscape, void of significant landmarks. However, if the last few months had taught me anything it was that the most remarkable things can be found and felt in the in the most unremarkable places.

We enjoyed a final breakfast in the relative luxury of our accommodation, filling our stomachs and our pockets while other guests around us ate their appropriately sized meals. The remainder of our morning was spent slowly packing our panniers, switching front and rear tires on my bike to best utilise any remaining tread, and a final supermarket stop. These activities had us leaving El Chalten by late morning. The road climbed gently out of town, making sure we could feel the accumulation of excessive eating, days off the bike, and some long walks in the mountains.

Looking back towards the Fitz Roy Massif, we were presented with one of the world’s most jaw dropping landscapes, subjectively and objectively. For me, these granite spires are woven together with tales of suffering and human endeavour, providing limitless motivation to continue exploring, pushing, and seeking adventure in this world. But regardless of an infatuation with exploration and extreme sports, it would be difficult for anyone to suppress feelings of insignificance and awe when faced with these rocks that have been shaped by the hands of heat, pressure and extreme weather over millions of years.

If it wasn’t for a healthy tailwind blowing us away from the mountains, we would have made very slow progress that morning as we stopped to look back every few minutes. After a few hours of pleasant riding over rolling hills we stopped in a ditch for a snack of sweet biscuits. The surrounding plains were becoming increasingly dry and barren the further west we pedalled. A pair of Chilean Hawks clung to a windswept bush behind us watching us like, well, hawks.

The wind was now whipping across the plains. Fortunately for us, it was still against our backs. Shortly after getting back on the road, we met three cyclists heading towards El Chalten. Their faces showed that they were not enjoying the benefitting from the strength of the wind in the same way we were, and they relished the opportunity to stop for a chat. Their separate adventures had converged near Ushuaia and they had now been riding together for about a month. Toby, from the UK, had his sights firmly set on making it to Alaska over the coming year. His bike setup was sleek. Custom made frame bags allowed all of his possessions to be neatly stowed away creating a streamline machine. This would have been an invaluable advantage riding into the strong Patagonian wind. Julian, an Argentinian guy with a rough plan of making it to Colombia, had a contrasting approach to packing. His bike was laden with different sized panniers, clothes, cooking utensils, and other trinkets hanging from any other available space. Notably, he had an assortment of large feathers attached to his handlebars, perhaps hoping for some extra natural lift. The third rider, Emma, hailed from Sweden. The most relaxed of the three, she was planning to ride until she doesn’t love it anymore. Simple.

Before parting ways, Toby was eager to share some advice and recommendations for the road ahead. All three of them were in agreeance that we must make the effort to visit El Calafate, a town on the edge of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. We’d soon come to learn what they meant by ‘make the effort’. He also confirmed what I’d been reading on various blogs about camping options on this current stretch of road. Due to the notorious winds and the little to no vegetation to provide any shelter, there seemed to be only one place to stay within the next 200 kilometres; the Pink Restaurant. Toby, Julian, and Emma said they had a great night there and that we would wouldn’t have any trouble getting a room!

We left them to continue their battle with the wind as we raced on to the junction with the Ruta 40. Being one of the longest highways in the world, stretching from Bolivia to southern Argentina, and with a reputation as one of the world’s great road trips, we had been anticipating an increase in traffic. What I hadn’t expected, however, was to discover the hitchhiker capital of the world! The edge of the road was scattered with backpackers holding signs decorated in various place names. Feelings of gratitude (and sheepishness) swirled within me as we pedalled by on our freedom machines, generating our own power and with complete autonomy over where we want to go!

These feelings were short-lived. From the junction with the Ruta 40, we began heading in a south westerly direction and the wind instantly went from friend to foe. Having been aided by the breeze all day since El Chalten, neither of us had really had to acknowledge the deep fatigue simmering within our bodies. The strong head wind caused a tsunami of lactic acid and within ten minutes of turning into the breeze we found ourselves huddled behind a pile of gravel on the side the road munching on chocolate.

We pushed on for another half an hour trying to find humour in the struggle. Roadside signs warning of strong winds seemed be an unnecessary use of resources. There was no reprieve and nowhere to hide. Running low on water, we were able to find a small dirt road down to the edge of Lago Viedma where we could fill our bottles and take shelter in the lee of another pile of gravel. The materials for road upgrades and maintenance were evident everywhere. If the workers were waiting for a day without wind, I can’t imagine much will ever be achieved out there. We made some lunch and threw stones at the bleached bones of a decayed carcass.

A slight bend in the road after lunch gifted us some favourable winds for the remainder of the day. The dry, rolling plains of pampas grass and bare earth was a textbook example of a rain shadow. The spine of mountains, still visible to the west, were now shrouded in dark clouds. These clouds, comprised of moisture carried in from the Pacific, would release their contents once they hit the mountains. This moisture, in the form of snow or rain, would then flow through rivers and streams back towards the ocean, creature the verdant paradise that we’d been riding through on the western side of the Andes. This process left very little moisture for the plant and animal species trying to survive on the eastern side. The result being the barren, arid, and unforgiving landscape that we were quickly learning not to take lightly.

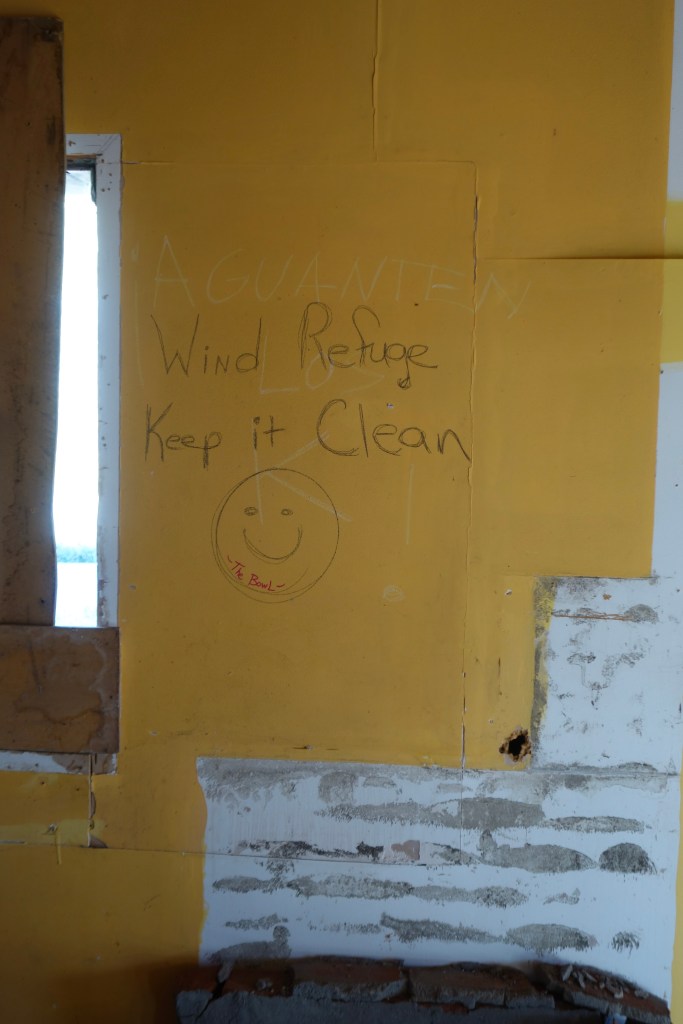

A welcome descent into a valley carved out by the Rio La Leona revealed the unmistakeable ‘Pink Restaurant’. According to a smashed and faded sign beside the road, what was now a renowned refuge for cyclists had once been a restaurant. All that remains now are the brick skeletons of two small buildings with flaking pink render, like a peeling, sunburnt corpse. Without doors, windows panes, or any other salvageable fittings, access into the buildings was simple. Toby had suggested we stay in the smaller of the two buildings. A quick look inside what appeared to be the original restaurant revealed smashed glass, piles of rubbish, and very little available floor space to spend the night. The other building, clearly the one favoured by cyclists, appeared relatively luxurious. The floor had been swept clean with a small broom that was lying in the corner, bricks and scrap timber had been used to create benches for sitting and cooking, and the walls were decorated with the drawings, names, and musings of fellow cyclists who had come before us. We wandered down to the river which also offered some beautiful camping options. However, with ominous floating on the horizon we committed to a night beneath the roof of the pink restaurant. As the sun dropped behind the hills, we began to notice some midges and mosquitoes also moving in for the night. We set up the tent and bivvy inside to maximise our chance of a peaceful night, cooked some pasta, and fell asleep very easily.

After a breakfast of porridge and a few instant coffees, we packed our bikes and tidied the room for the next cyclists seeking refuge from the Patagonian winds. After making a few adjustments to my bike outside, I walked back in to find Dad busily contributing to the graffiti on the walls. He was truly embracing life on the road now.

We had 70 kilometres left on the Ruta 40 before reaching the junction to El Calfate. From the restaurant, we pushed our bikes up the gravel path to meet the highway. Emerging from the sheltered river valley, we were hit in the face with the wind that was already whipping across the plains. Fortunately, the wind was heading in the same direction as us and we took off down the road, literally.

The riding was sensational. Fierce looking clouds covered the mountains to our west but we were soaked in morning sun. With the help of the wind, we reached speeds of 80km/h whenever the road took a slight decline. Any doglegs back into the wind gave us a harsh taste of reality and ensured we remained grateful for nature’s helping hands. At one point, I took a swig of water to wash some dust from my mouth. Spitting out the water, it remained suspended beside me in the air before dissipating. If I was travelling forward at around 60km/h, then the wind was doing at least the same. It was insane!

Travelling at high speed allowed us to keep up with some of the unique wildlife living in the region. We raced flocks of rhea (South American ostrich) along the road, marvelling at their grace as they strode beside us with ease. Every muscle and tendon in their legs rippled with definition like the hind legs of a grey hound. Our presence startled grazing herds of guanaco; another species of hump-less South American camel. Springing like deer through the tussocks, the guanaco floated over wire fences that attempted to impose boundaries on this untameable landscape. Occasionally, we’d pass remnants of those that had snagged a leg in their attempt to clear a fence. Lacking the poise of their other herd members, these guanacos had become condor fodder, with nothing but their skeletons and skins left blowing in the wind.

A roadside lookout providing views over Lago Argentina gave us reason to pull on the brakes and take a break. As we sipped water and marvelled at the liquid silver surface of the lake reflecting shards of sunlight, we were approached by a merry band of elderly travellers. The group of friends, travelling in a small convoy of cars, were from Chile, Belgium, and France. One particular lady made Dad blush when she refused to believe he was old enough to be my dad. He even took off his helmet to use his hairline as evidence for his true age but she was still not convinced, saying that she wanted whatever he was taking. The unspoken flipside of this interaction was that she didn’t believe Dad was old enough to be the father of someone who looked as old and haggard as me. I let Dad have his moment. The whole experience left him riding on a wave of grotesque confidence. As we continued sailing down the road, he jabbered on about how he must be causing marital issues for every couple that drives past. “The wives mustn’t be able to take their eyes off me…the poor husbands must be under so much pressure to look like me…even the husbands must struggle to keep their eyes on the road…” I pulled ahead to let him bask in his new found bravado.

Including several stops, we covered the 70 kilometres to the junction in a little under two hours. We knew that from here we’d be riding into the wind for the remainder of the day. A large drainpipe offered some shelter for us to make a coffee and summon the energy for what was to come.

The next few hours took more willpower and energy than each of us had individually. Together, however, we were pretty impressive. We alternated being at the front, taking 10-minute turns being both the wind break and the motivation for the person behind. This continued for the first hour without conversation, partly due to a lack of energy and also the fact that any words were stolen by the wind.

A fast-approaching couple on a tandem bike gave us a reason to take our first break. Miriam and Max, a French couple, had been in El Calafate to pay a fine they had received in El Chalten for walking a particular trail without a permit. I couldn’t imagine having to ride this brutal stretch for bureaucracy rather than ‘pleasure’. They said they had just covered what took them two hours yesterday, in 25 minutes. In fact, they were actually frightened by the strength of the tail wind, saying they had been using their brakes to slow down.

When we needed it most, this stretch of road was void of infrastructure, vegetation, and anything offering a windbreak. Fortunately, a lone building at the junction to the local airport provided a chance to stop for lunch and collect our thoughts. There really wasn’t much to talk about. It went without saying that neither of us had ever experienced wind this strong, let alone tried to ride our bikes into it. If only we knew what was still to come.

The remaining 25 kilometres from the airport junction to El Calafate was nothing short of barbaric. The wind found another gear and the amount of traffic increased with vehicles travelling to and from the airport. Trucks and busses created additional and unexpected gusts of wind that tried to force us from the road. However, it is the momentary wind shadow left behind by these vehicles that is most dangerous and causes you to drift back onto the road towards the traffic. There were genuine moments of fear as some vehicles passed treacherously close to our handlebars.

Being passed by so many vehicles heading to our destination, I gestured to Dad to pull over so I could pose what I thought was an obvious question.

‘Should we stop and try and get a lift’, I asked, despondently.

Dad took a moment to respond, taking a long drink and wiping the sweat and dust from his glasses. He looked beaten. However, his response was legendary.

‘I’d rather walk than get a lift’, he said as he pushed off and continued the battle.

The final 20 kilometres of riding required an inspired effort and I couldn’t have been more in awe of Dad. The tree-lined streets of El Calafate were a welcome sight. We rode straight to Los Dos Pinos, another campsite recommended by Toby, and set up the tent in a small garden of cherry trees protected by high hedges. We then indulged in long, hot showers to wash away the grime and tension of the last two days.

The soundscape of our past few days had been dominated by howling wind, heavy breathing, sudden gasps as vehicles shot past, and the occasional scream of encouragement from the passengers of passing cars. However, there had been another subtle yet metronomic creaking coming from bowels of Dad’s bike. Finding and fixing the cause of this sound had become an increasing priority, especially as the tough conditions had caused our irritability and intolerance to rise. We had tried tightening everything we could with the tools we were carrying, but the sound persisted.

Google Maps showed one mechanico in town so we hopped back on the bikes and made our way to the address. What we found was a normal suburban house showing no signs of grease or overalls, or anything else to suggest the presence of a mechanic. I knocked on the door but no one was home. Before giving up and leaving the suburb, we pushed our bikes down to a corner shop at the end of the street to see if the owner could shed any light on the whereabouts of the town mechanic. Surprisingly, the woman inside walked me back on to the street and pointed to the house we’d visited. She said it was in fact where we could find the mechanic but that he wouldn’t be open until tomorrow. The language barrier still left us wondering if the house was where the mechanic worked or it was just his house. We thanked her for her help and decided to continue the task of bike maintenance tomorrow. After the day we’d had there was only one thing either of us really felt pursuing – beer.

We rode back to the main street and happened upon La Zorro, a local craft beer bar serving everything from strong floral pale ales to heavy, malt-laden stouts that could serve as a substitute for food. As we tried to focus our depleted brains and make the simple decision of what beer we wanted to drink, we struck up a conversation with a girl called Mikayla from Newfoundland, Canada. More accurately, she struck up a conversation with us. More accurately again, it was less of a two-way conversation and more a monologue. This suited us though, as our capacity for socialising was fairly low. Mikayla was trying to sell her bike while in El Calafate. She’d ridden and bussed from Peru with persistent knee pain and had finally decided that it was all getting too much. We listened for an hour or so as it became increasingly obvious that she was feeling pretty lonely. I could empathise having experienced the same feelings for the months before Dad’s arrival.

After a few beers and a dinner of vegetarian waffles, we headed for the campsite. I left Dad to walk back alone while I swung by a supermarket to get some things for breakfast. Back at the tent, we sat and ate some sweet biscuits and chatted to a French couple who’d just been reunited after a few months apart. She had been completing an exchange program at a university in Chile and he had been hitchhiking from Bogota. He’d arrive in El Calafate that morning after 60 different rides, ranging from long-haul trucks to the backseat of motorbikes.

Exhausted and sufficiently buzzed, we craved rest. My last vision that evening was Dad moving back and forth between bags trying to get organised for bed, with his sleeping bag liner draped over his shoulders and the solar lamp held out in front for light. Dreams of Florence Nightingale ensued.

The opportunity to experience the grandeur of the southern Patagonian Ice Field is what had lured us to this corner of Argentina. El Calafate serves as a gateway to the Los Glaciares National Park which is home to the Perito Moreno Glacier, among many other great tongues of ice. The terminus of Perito Moreno sits around 80 kilometres west of El Calafate. Our initial plan had been to ride there but, after tasting the region’s relentless westerly winds, we had decided to treat ourselves and organise a driver for the day. When we’d checked in to the campsite upon arriving in El Calafate, the manager had booked us a seat on a bus for the following morning.

We emerged from the tent dehydrated, tired, and a little hungover. After cleaning up the campsite and cooking some porridge, we headed to the front office to wait for our bus. At 9am, a bus pulled up and the energetic driver holding a clipboard hopped out and told us to hop in. As we took our seats, I asked him if he needed to check our names, which he did and quickly discovered that we weren’t meant to be on his bus. We climbed off and let the other couple waiting in the front office to climb on and take the seats that were meant for them. Five minutes later a taxi pulled in and the campsite manager came out and pointed at it telling us that this was our ‘bus’.

The road towards the national park dissected windswept plains and the driver sporadically pointed out various birds of prey. Sitting in the backseat of a car as the kilometres evaporated with ease caused another surge of gratitude for the freedom gifted by our bikes and bodies. I felt so in tune and connected with the landscape, weather and wildlife; things that those travelling in the comfort of vehicles may not have the luxury of experiencing.

The driver stopped at the border of the national park and handed over the money we’d given him for the entrance fee. The edge of the park marked a sudden change in vegetation and topography. Folds and creases in the landscape increased while beech forests and flowing creeks became more abundant. It felt Tasmanian and inviting. However, with the narrow road, amount of tourist traffic, and the howling wind, we were still happy to be having a day off the bikes.

We soon arrived at the main visitor centre and, after parking the car, the driver turned to us and asked us to be back in “two, three, or four hours”. As crowds headed for the glacier, we dragged ourselves to the giftshop café for a coffee to go with a few leftover biscuits I’d found in my bag. The car trip had caused our bodies to stiffen and had allowed our minds to switch off. We drank our coffees sitting on a stone wall with our faces to the glacial winds. It didn’t take long for the immensity of the surrounding natural forces and phenomena to drag us from our stupor.

The next three hours were spent wandering along an elevated timber walkway that meandered through an ancient beech forest. Perfectly positioned balconies offered varying perspectives of the glacier’s terminal face. We sat on every available bench in an attempt to truly absorb what lay before us. The 30km long tongue of ice – a cracked and crevassed slave to gravity – is one of 48 glaciers within the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. The ice field itself is the world’s third largest reserve of fresh water.

The varying shades of blue told stories of seasons past. What would have fallen as snow hundreds or thousands of years ago, had now been compressed during a journey from the high valleys to the terminus where ice meets sea. This ancient ice, like piercing blue eyes, stared out of the glacier with wisdom and purity. Swirling tones of deep iridescent blues sat below more opaque ice and the brilliant white of fresher snow which dusted the surface of the glacier. The visuals were overwhelming. However, it was the soundscape that left the deepest impression on my soul.

Excited conversations were continually interrupted by the relentless creaking and cracking coming from deep within the ice. The tension – accumulated over centuries of freezing, thawing, growing, shrinking, gliding, and grinding – was palpable and haunting. Nerve-wracking volatility engulfed the crowds of tourists with each gunshot cracking of ice. We sat for a long time, entranced by the sporadic calving of ice pillars as they tore free from the terminal face and plunged into the hungry ocean below.

While peeling boiled eggs and stuffing them into bread rolls for lunch, we watched as a tourist boat approached the glacier with trepidation, trying to gift its passengers a unique and intimate view of the ice. As the boat came within a hundred metres of the glacier, a frozen tower peeled from the face and fell into the ocean creating a concerningly large wave. The boat instantly swung around and motored at pace to outrun the swell. This pattern of cautious approach and rapid retreat continued for an hour, the boat like a nervous seagull trying to get increasingly closer to someone eating chips at the beach.

We moseyed back to the carpark to meet our driver who was parked in the same spot. He told us that we were waiting on two more people for the drive back to town. The others passengers, a mother and daughter travelling together through Argentina for a few weeks, soon arrived with glasses of whisky poured over glacier ice. We buckled up and made a token attempt at small talk before succumbing to the heat in the car and falling asleep for the remainder of the drive.

Back at camp in El Calafate, we made a late afternoon coffee to summon any dormant energy that may have still been lying deep within our bodies and minds. Dad sat and tinkered with his bike for a while, eventually removing a plastic cap on the crank arm to discover that the bolt within was super loose. The fact the creaking was coming from a loose bolt rather that a deteriorating bottom bracket was an uplifting diagnosis. However, we didn’t have the tools to tighten the culprit. We rode to a petrol station with an attached workshop, but after much discussion and charades the mechanics still refused to let us use any tools, let alone pay any attention to a form of transport without an engine. After riding around for another 20 minutes, we came across a derelict looking garage. It could have been the set for a nineties pop music video. Several men sat around jacked up cars with their overalls rolled down to their waists, showing their grease covered arms in dirty white singlets, each with a bandana tied around their heads. I rolled up to them and began my best Britney Spears impersonation which prompted them to all stand up and begin dancing and washing the cars with soapy sponges. While this was going on, Dad borrowed a 10mm allen key and tighten the crank arm. A simple solution to a lingering problem. We rode back to La Zorro to celebrate with a beer.

Perched in the window of the bar with a fresh pale ale in hand, we watched the world roll by and contemplated our next moves on our journey south. Half way through our beers, we locked eyes with a group of familiar looking men as they were walking past. We’d met two of them a few weeks earlier in the campsite in Coyhaique. They had been making their way down the Carretera Austral by local bus, travelling light and camping wherever possible. Dad had enjoyed a lengthy chat with the men as they were relishing their recent retirements – a lifestyle I could tell was becoming increasingly appealing to dad with each day on the road. The guys waved to us and changed course to come into the bar for a chat. They were on their way out for dinner so declined our offer to settle in for a beer. However, they were eager to hear how our trip had been since we’d last seen each other. They introduced us to their companion, Tyler, who was also travelling by bike. Tyler was from Montana and had spent the last month cycling through Argentina, from Bariloche to El Calafate. He was flying home the next morning. Despite admitting to have done ‘a little bit’ of road cycling, he told us that he was new to cycle touring and peppered us with questions, heeding our responses. He complimented me on reaching 7000km and on the length of my beard. We chatted for ten minutes or so before the three of them continued on their way to dinner. As soon as they left, Dad and I looked at each other and without words could tell we were thinking the same thing; how do we know that guy?

Tyler was so familiar. We banged our heads together over another beer, trying to work out how we knew him. When the answer came to us, we sat in a daze of retrospective awe. We’d just met Tyler Hamilton. The Tyler Hamilton. The Tyler Hamilton who was a close teammate of Lance Armstrong in Armstrong’s 1999, 2000, and 2001 Tour De France victories. The Tyler Hamilton who won Olympic gold in the individual time trial. The Tyler Hamilton who rode the 2002 Tour of Italy with a broken shoulder, finishing second overall but dealing with the pain by grinding his teeth so hard that he had 11 of them capped or replaced following the race. The Tyler Hamilton that co-authored a book (The Secret Race: Inside the Hidden World of the Tour de France: Doping, Cover-ups, and Winning at All Costs), detailing his battle with clinical depression, his decision to participate in an infamous doping regime that eventually had him exiled from the sport, and his complicated relationship with Armstrong. I’d read this book several years earlier and, like all readers, had been enthralled by Tyler’s courageous and determined effort to reveal the hard truths about the sport in which he’d once given everything to be successful.

Just a little starstruck, we spent the remaining hours of the evening hypothesising about all the questions we could have asked Tyler had we known who we were talking to at the time. But, on reflection, the conversation we had shared had been so honest, authentic, and normal. I have no doubt, given his story and relationship with the sport of cycling, that he was relishing the opportunity to be riding his bike for pleasure in a foreign country, just like we were doing. My favourite memory of our interaction with Tyler Hamilton remains the fact he said he’d done ‘a little bit’ of road cycling.

We left the bar and rode back to the campsite to cook up a vegetable curry for dinner. In the camp kitchen we met an Israeli guy who told us his story of flying to Buenos Aires to watch River Plate take on Boca Juniors, only to have it cancelled due to bad weather. This was the same game of soccer that had been the talk of the hostel when I was staying in Valparaiso. It is one of the most famous rivalries in world soccer due to the fact that the two clubs are located only 7 kilometres from each other yet approximately 73 percent of Argentinians support one of the two teams. Despite paying over $2000 in flights to attend the cancelled game, he told us that it was still one of the best experiences of his life. This was because he’d been interviewed by an Israeli TV channel. During the interview, he’d made a joke which had subsequently gone ‘viral’ in Israel. He was ecstatic that the clip had over 10,000 views online and that he is now an Israeli internet sensation. We let him talk, not wanting to burst his bubble by telling him that we’d just met an actual superstar. We’d met Tyler Hamilton.